How to take meeting notes

How I trained myself to remember 95% of a 2h meeting.

I’ve spent August figuring out how learning works and how we can apply spatial cognition and computers to improve how we learn. And I’ve got some pretty exciting stuff coming out in the next few weeks. Spoiler: if you’ve ever tried learning how to program but failed miserably, you’ll appreciate this even more.

But today I want to talk memory.

A few months back, I’ve started taking extensive meeting notes as a part of my memory experiment. In four weeks, I trained myself to remember about 90-95% of everything that happens at a meeting. And I’m still fascinated by how delighted people are to receive a detailed note with everything we discussed (ideas, concepts, projects, etc.).

After polishing my method for two months, I’m now ready to share it with you. Here’s why you might be interested:

- Taking meeting notes improves your long-term memory through active recall [1]

- You can delight the people you meet with by sending a detailed note with everything you covered on a meeting (very few people do that)

- You can foster relationships with friends by sharing relevant meeting notes around

- You can turn meeting notes into novel, relevant, and personalized content for your audience

Enjoy your reading & take better notes,

- V

How I take meeting notes

I do not take notes during the meeting. I’ve tried this many times and always found it to be distracting. I couldn’t concentrate on writing and listening to the person at the same time. This led to bad notes and poor conversation.

Instead, I take notes after the meeting. Whenever I meet someone, I try to pay attention to what they’re saying and be fully engaged. If I’m taking this meeting, then I better pay attention to it. And if it’s not worth my full attention, then I shouldn’t spend time on it.

Step 1: Descriptive writing

Immediately after I come back home, I sit down and pull out a piece of paper and my iPad with the Drafts app.

In Drafts, I begin what I call descriptive writing. I write in the first person just about everything I remember from the meeting. Usually, to get going, I begin with something like:

“Just came back from meeting such and such, we went to this nice new sushi place in the city that just opened a few weeks back..”

Writing from the first person helps avoid the writer’s block that arises because you’re trying to convert the stuff you hear in your head (in the first person) into the stuff how it’s supposed to be written (in the third person) [2].

The purpose of recalling these seemingly irrelevant details is to activate the brain’s areas that store information that you need. In a technical language, to use implicit memories of space, things, and faces to increase the likelihood of recalling more abstract things like ideas and concepts.

Here’s how my Drafts file looks like when I begin recalling ideas:

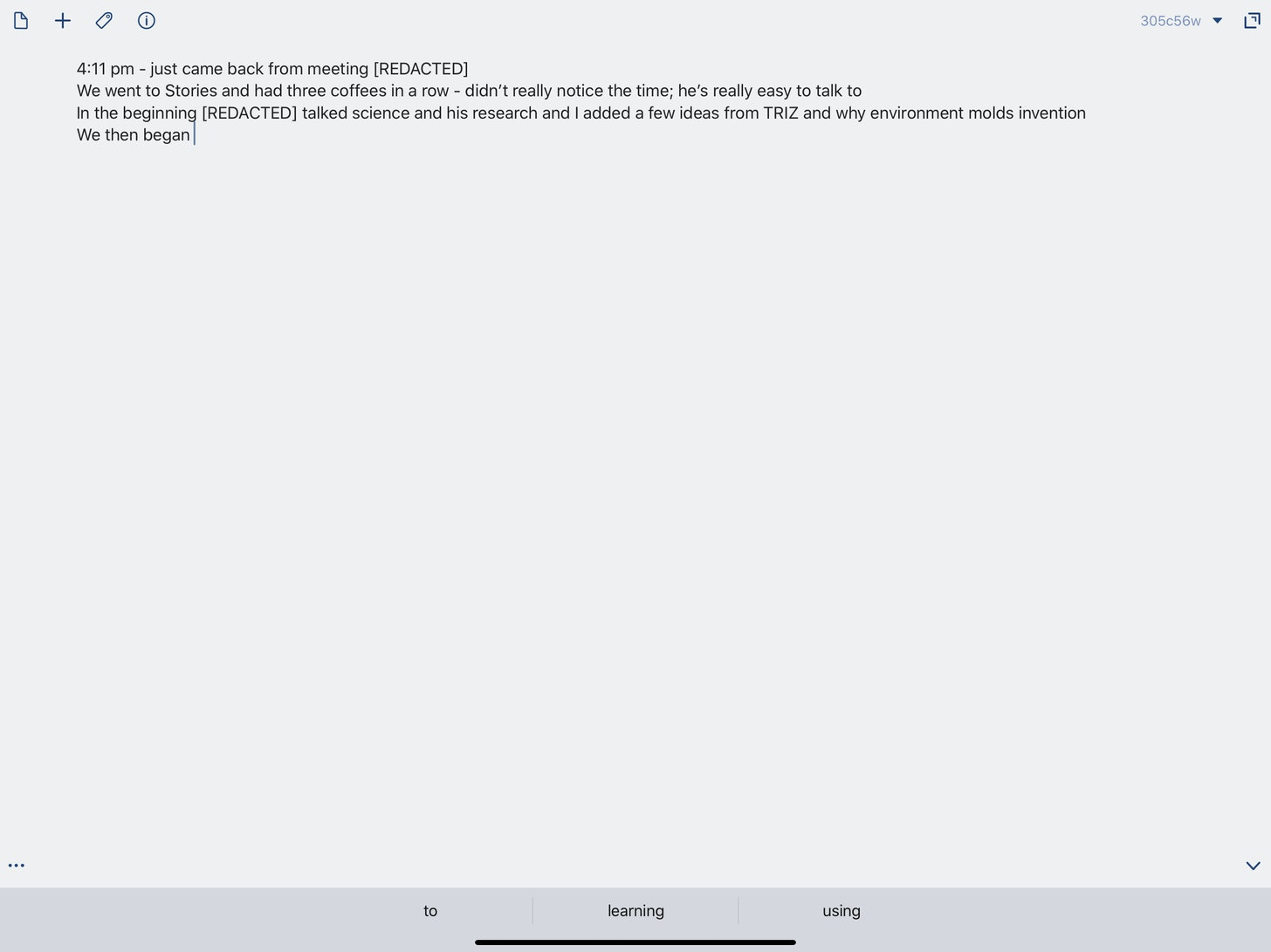

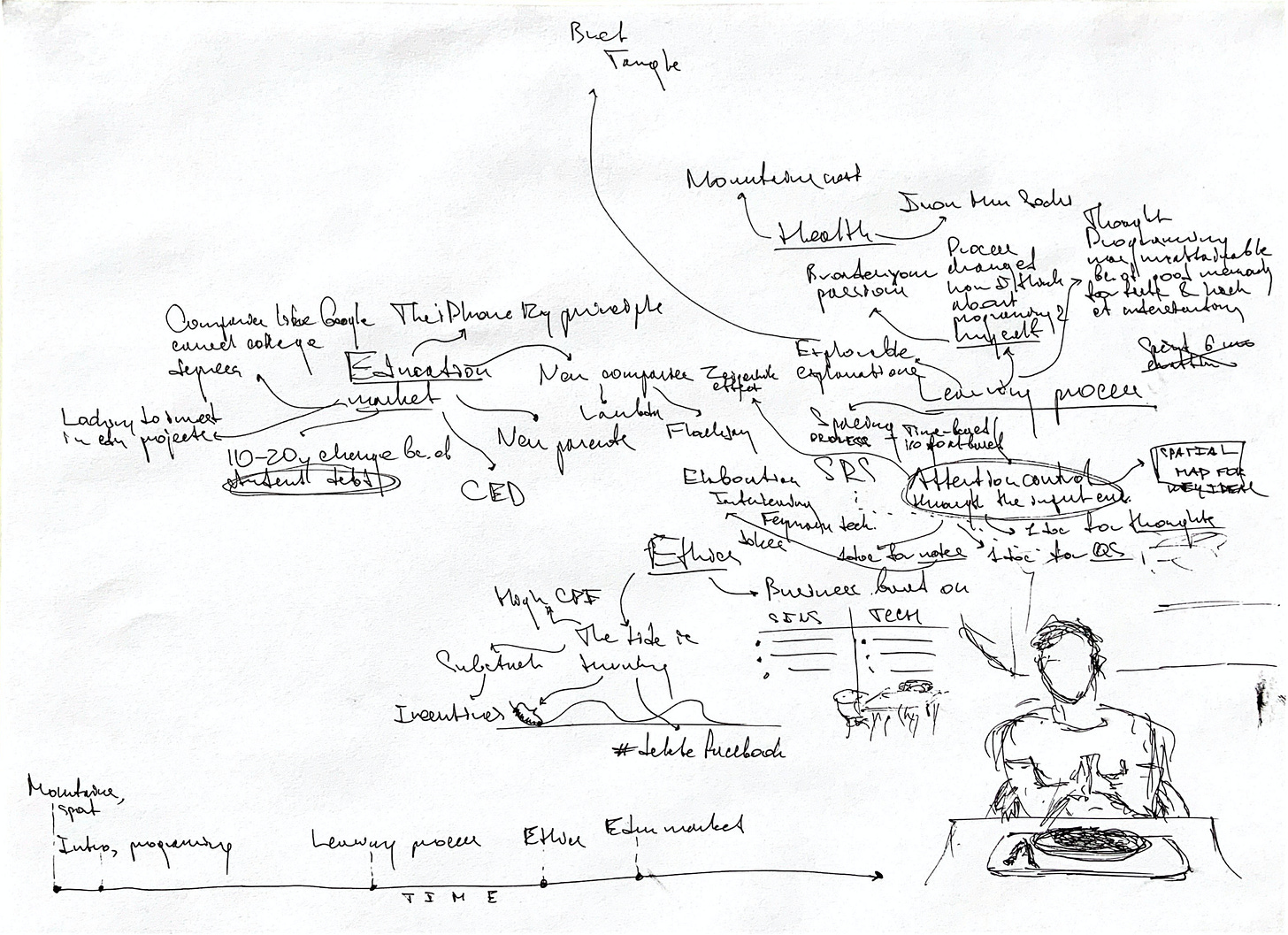

Step 2: Spatial cognition & categories

Once I get going, I turn to my piece of paper and start writing & sketching concepts and ideas that I remember from the meeting. I do not write them in a list; instead, I scatter them around the paper piece and use lots of rough sketches, arrows, lines, and boxes. This leads to enhanced spatial cognition because I can see unobvious relations between ideas that are impossible to see in a list view.

Here’s how my paper notes look like when I’m in the middle of the recall process:

I begin from any level here. If we talked about education for two hours, but I remembered the marathon that we discussed when we were ordering food first, I’d jot down the marathon first. On this step, I use categories [3] to pull out even more memories from my head. If we talked about nutrition, I’d tell myself:

“OK I remember we’ve talked about nutrition, but what’s the next layer above nutrition? Oh, that’s health. And have we talked about anything else health-related such as fitness? Oh yeah, marathons!”

I switch back and forth between the two interfaces but spend 90% of my time on paper because of how powerful it is. It just feels different. Unfortunately, there’s no software for thinking that uses more than two modes of thought [4].

I also do not write fully formed sentences on paper; they’re more like hooks to remember things when I’ll be writing a note. I suspect this also helps to compress ideas into chunks, which leads to higher speed of thought (that is audacious speculation, I know).

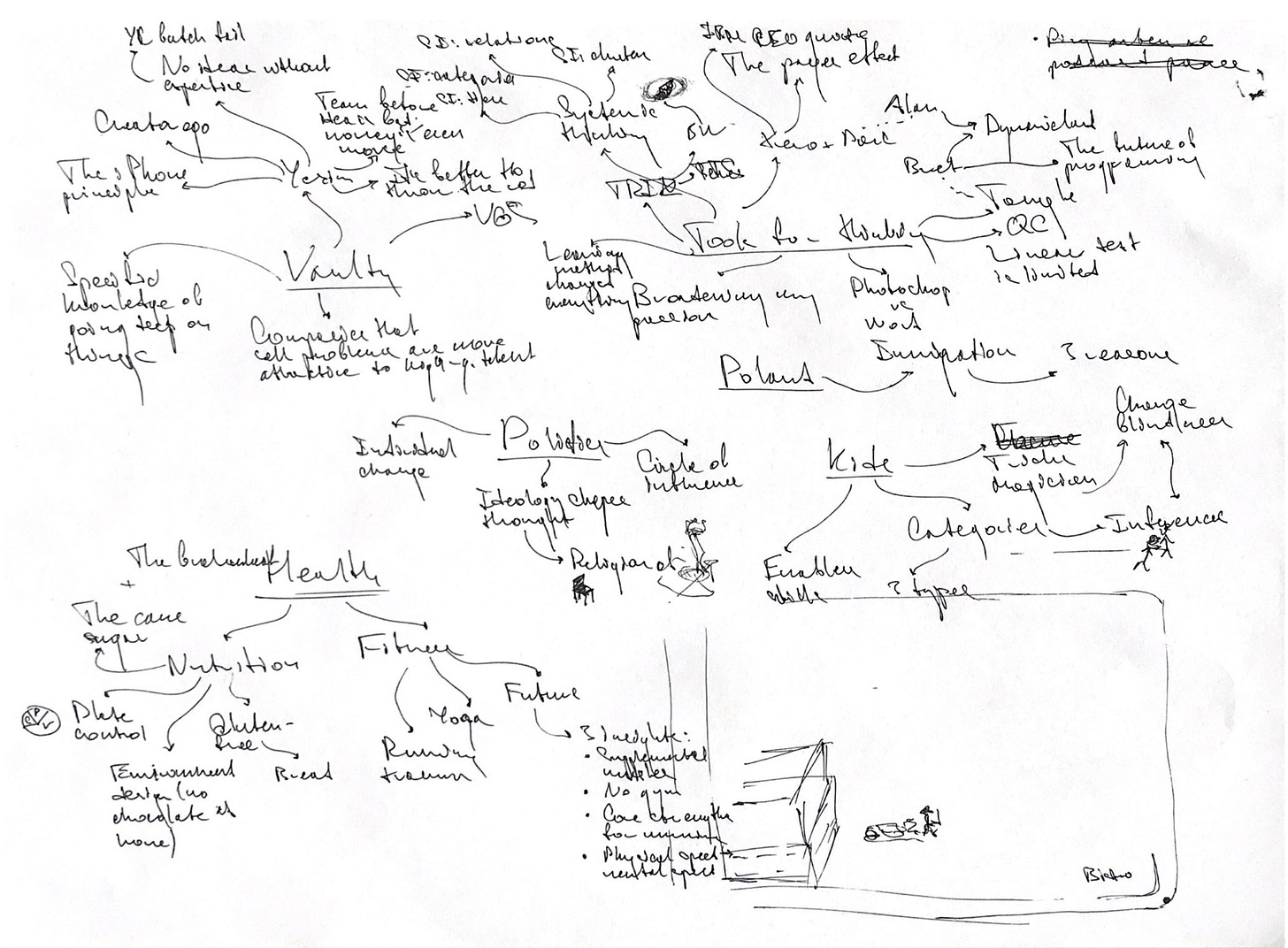

Step 3: Sketches, maps, and timelines

Once I feel like I’m slowing down (usually after 5-7 minutes of doing the Drafts/paper part), I begin doing three other things: drawing the person, drawing the map, and drawing the timeline.

Here’s how it looks:

First, I sketch the person in the bottom right corner of the piece of paper. Drawing helps me bring back many other emotion-related things because I begin remembering emotions I’ve implicitly stored (i.e., when the person was angry, happy, loud, etc.). I’m by no means good at drawing, but the idea is to produce at least a somewhat close representation of a person as you can get to aid your mind with recalling thoughts. See the image above for details.

Second, I draw a map of where we’ve been. If we went for a walk, I draw a map of the space that we covered. If we were inside, I draw a map of the room we were sitting in. Creating a map helps activate the brain’s area responsible for space, and I get many memories out of it [5]. Plus, it’s a lot of fun!

One interesting observation here: whenever I draw a visual representation of the place (i.e., if it’s a coffee shop, then tables, other people around, the bar, etc.), I begin recalling space-related ideas that we’ve covered with the person (i.e., countries, travel, routes, even loosely related things like the biography of a person who lived somewhere). I don’t yet know how to explain this, but it works every time. Last week, when I watched Peter Thiel’s speech at the WIRED UK, and I jot down the scene, I instantly began remembering how he talked about China and new cities in the ocean; all space-related ideas from the talk.

Third, I draw a horizontal timeline diagram of the meeting and map different things that we covered on that timeline. I haven’t figured out how this works yet, but drawing a timeline and then mapping various conversation topics helps to identify things that were before or after this particular topic in time, left or right on the timeline. The timeline also uncovers additional ideas that I missed. In addition to that, I go forward and back in time when I’m recalling concepts. I try to remember things sequentially, both from the beginning and from the end of the meeting.

Once I feel like I’ve reached a critical mass and hit the inflection point of understanding what the meeting was about, I get back to my input environment, Drafts, and start writing notes. I’m bilingual and meet with many Russian-speaking folks, so I write in Russian if I need to. During the spatial thinking process on paper, I usually identify clusters such as “education” or “health”, and draw a circle around them to make them stand out. So when I begin writing textual notes in my input environment, I start from those clusters and use them as section titles, such as Notes--Education or Notes--Health. Clustering seems to improve my ability to recall things that were left behind when I was doing the spatial thinking process and visual thinking with illustrations. Another interesting observation is that clustering helps to connect ideas from the meeting to my own thinking, supposedly because I focus my attention on the things I’m writing, which triggers associative thought.

The whole process takes about 30 minutes per 1.5-2h meeting. When I finish writing notes, I add materials that I think are relevant to what we covered. As a result, I get about 500 words with links that I send to the person.

Here’s how a full notes file looks like (in Russian):

How to begin taking meeting notes

To build a habit, you need to tie the process of taking meeting notes to a specific thing you do with no exception. For example, you can commit to begin writing meeting notes immediately after returning home and getting your shoes off. That’s how you make it stick [6].

As for the process itself, this is something you learn best by doing. So whenever you meet someone, try to pay attention to what the person is saying. There’s no need to use special mnemonics or convulsively writing down notes.

Once you come back home and take your shoes off, do the following:

- Open up your favorite text editor on your computer or phone

- Find a piece of paper and a pen (I use plain white A4 paper and a black gel pen); paper needs to be disposable so that you wouldn’t be afraid to sketch things and go really fast

- Begin writing in your text editor; if you don’t know what to write or don’t seem to remember anything, begin describing the previous 5-10 minutes in the first tense and ideas will come. For example, “Just came back home after meeting such and such, we’ve been to such and such place and had such and such food”

- Once you begin remembering things, jump to the piece of paper and continue thinking there instead of writing them in the input environment; this will unlock a new stream of ideas and help you see new things because of spatial cognition

- Apply categories, drawings, maps, and timelines to bring back even more exciting ideas

- Continue switching the interfaces until you feel like you’ve got enough written on paper

- Jump to your text editor and write notes based on what you have on paper

- Add relevant links and materials and send to the person

How to turn meeting notes into content

After months of taking notes, I’ve figured that meeting notes are a unique content type. I’ve begun editing them slightly to omit personal details and sending them to people who I thought would be interested. It worked surprisingly well; from ~150 people I shared a note with about 95% replied and said they loved it.

The big learning is that meeting notes might be an interesting new content type that people aren’t yet bored with.

Here’s why:

- Novelty. We don’t repeat things at meetings because we know the person already knows them.

- Relevance. We talk about things & ideas that are interesting to both parties; we understand this by tracking hundreds of signals from their face, body language, and words in real time. On Facebook, the only feedback channel is likes; I don’t see their “meh” faces when they’re reading my stuff and can’t understand what kind of reaction my ideas trigger.

- Quality. The quality of information shared during the meeting is higher than in one-to-many publishing on Facebook.

- Personalization. Sharing ideas with people I know loosely and adding a personal touch (i.e., “hey I thought this would be interesting to you because..”) increases the probability of a note to be read, which, in turn, increases the likelihood of the learning process hierarchy to be completed, changes in the long-term memory created, and transfer to real life occurred.

- Channels. More and more people stop using socials for content discovery because of ads/low-quality information. This change suggests there’s an opportunity for a new, more personal channel.

That’s why I’m doing an experiment and putting my meeting notes online. You can subscribe to receive updates by clicking here. Whenever I meet someone, I’ll email you my meeting notes (approximately once in 2 weeks).

Other thoughts that didn’t fit the main storyline

- It seems that the process trains my mental machinery to pay attention; I have no proof but my remembering accuracy (how much I can bring back) and ease of recall has increased ~2-4x after two months of doing this; I’m now able to recall about 90-95% of a meeting.

- The use of different categories of information (i.e., questions we discussed, when a person was angry or excited or happy, concepts we covered, mathematical notations we applied such as graphs or matrixes or spectrums, people we referenced, etc.) seems to help with remembering by dissecting the whole body of things we covered into different dimensions and sectors. I’m curious about how this first-time active recall aids impact long-term memory; because things that make the cognitive process easier usually don’t get remembered well.

I use the same process and three reflections questions to any piece of content that I consume, and it works exceptionally well. When I finish reading or watching something, I ask myself:

- What are the key ideas?

- How can I apply this knowledge that I learned?

- How do these ideas relate to what I already know?

[1] A good place to jump into relevant active recall studies is this Wiki page.

[2] I suspect the term came from Stephen King, but it’s also very often referred to as “Dear Joel.”

[3] For more information on categories, refer to Barbara Tversky’s Mind in Motion book, p.35 & p.51.

[4] My dad designs furniture for 30 years and he feels the same about AutoCAD. If you’d like to learn more about modes of thought and how we ended up constraining ourselves in a small rectangle that sits on a table, watch this talk from Bret Victor.

[5] For more information on how grid cells work, Barbara Tversky’s Mind in Motion book, p.69.

[6] And yes, such sequencing works for any habit.